Introduction

In the Meiji era, Japan rapidly embarked on a path of modernization. New technologies and cultures from the West poured into the country, transforming how people lived—and how they spent their leisure time. Among the many visual media that emerged during this period, the gentō (magic lantern) was especially significant.

This device, which used light to project images onto a screen, was not only a form of entertainment but also a tool for learning. One remarkable work that captured the dreams and aspirations of Meiji-era women through the lens of gentō was Gentō Shashin Kurabe (Magic Lantern: A Contest of True Images), a series by the ukiyo-e artist Yōshū Chikanobu.

Comparing with Nozoki Karakuri

The gentō shared similarities with another popular visual entertainment device of the time—the nozoki karakuri. This “peep-show” mechanism, enjoyed since the Edo period, invited viewers to peer into a small box to see vivid, layered illustrations, often accompanied by narration.

However, while nozoki karakuri involved a private act of looking inward, the gentō shifted the gaze outward. It projected images into a shared space, allowing audiences to experience visuals together. This evolution—from individual peeking to communal projection—helped the gentō expand beyond mere entertainment into the realms of education and public enlightenment.

The Educational Role of Gentō

The Meiji government emphasized education as a cornerstone of building a modern nation. The gentō, with its visual clarity and accessibility, became an ideal teaching aid. Slides showing scientific diagrams, world maps, and historical events were used in schools, turning gentō into a kind of “illuminated textbook” for children.

As traditional terakoya schools and wasan (Japanese mathematics) were replaced by Western-style education, gentō lantern shows became symbols of modern learning. When a gentō show was scheduled at school, children would rush home to tell their families, and entire households would gather to attend the evening event.

The Dreams of Women in Shashin Kurabe

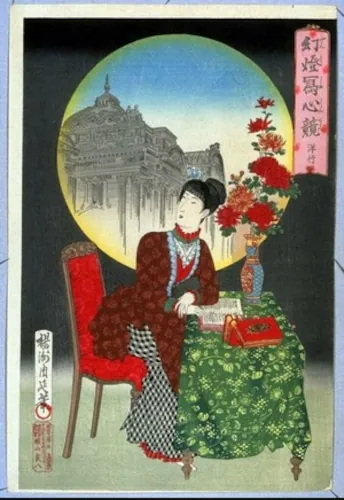

Against this backdrop of expanding gentō culture, Chikanobu’s Gentō Shashin Kurabe series emerged. In each print, the dreams of Meiji-era women are depicted within a round frame, resembling the circle of light cast by a magic lantern.

One print shows a woman in elegant Western dress, gazing wistfully at a scene of Paris projected behind her. In another, a bride-to-be sits quietly, while her dream—herself in a traditional wedding kimono—glows softly in the background. These circular dreamscapes act as windows into the desires and imagined futures of women navigating a rapidly changing world.

The Modernization of Seeing

The gentō transformed not only what people saw but how they saw it. In earlier times, visual culture centered on scrolls and ukiyo-e prints, viewed by hand. With gentō, images were no longer held—they were projected. This shift marked more than just a technical change: it represented a new way of engaging with the world.

Looking was no longer a solitary, inward-facing act; it became a shared, outward-looking experience. The public gaze was born, opening people’s eyes to new ideas, places, and dreams.

Conclusion

The gentō was a beam of light that illuminated the dreams of the Meiji era. It delighted audiences, educated children, and offered a glimpse of modernity through shared visual experiences. Chikanobu’s Gentō Shashin Kurabe beautifully captured that light, gently revealing the hopes and desires of women living through a time of great change.

If nozoki karakuri drew viewers deep into the heart of a story, the gentō opened a window onto the stage of modern life itself. What kinds of futures did people imagine as they gazed through that glowing circle of light?

References

- Tokyo Museum Collection: https://museumcollection.tokyo/works/6242856/

- Yokohama Museum of Art – Viewing Guide: https://yokohama.art.museum/special/2017/fashionandart/pdf/yoshu_2.pdf

- Kyōiku Jihō (Educational Bulletin), No. 419, Tokyo Metropolitan Educational Research Institute, Dec. 1982

- Komura Kobune, Stories of Meiji-Era Youth Culture

Comment